“What happens when we let go of our traditions? We become new ones.” In her Outernational Listening Session “Sounding Changes” at Radialsystem Berlin, Wendy M. K. Shaw thinks about such becoming through letting go. Change is a vital theme for her, a scholar of the art of Islamic cultures, whose most recent book, “What is ‘Islamic’ Art? Between Religion and Perception,” attempts to transform our understanding of how perception functioned in the pre-colonial Islamic world. Letting go of conventional categories for the arts, she considers music to understand images and representation in a culture whose primary sensory organ was the heart. How can her work be used as a toolbox for artists and musicians, who are looking for means of sliding free from the straightjackets of cultural and genre categories? And what’s the sound of a decolonized music practice? A conversation about cultural change through time traveling to the past, the connections of listening and seeing, and how Islamic ornament can serve the decolonization of music.

By Philip Geisler

Title Image © Erik Albers

Your current research evolves around the question of what pre-modern “Islamic” art is. Why do you deal with music in order find out about that?

While public discussions of Islam often talk about an image prohibition, there have been many pictures in Islamic cultures. This misconception is pretty surprising – I try to address how it emerged and persists, but what is more interesting to me is how people understand these images as producing meaning. As I was investigating this question for the image in Islam by reading the Qur’an, religious commentaries, philosophy, and poetry, I realized that limiting art through the visual image, privileging vision in that way, is a modern European practice. As in antiquity, in a tradition that travels through the thought of Plato into Late Antiquity in which Islam emerged, the heart, not the eye, was the primary sensory organ, and the ear was a central vehicle to it. Most early commentaries about permissibility of the arts in Islam are about music. These give a good idea about how music was understood as intoxicating, potentially leading people astray but also potentially leading them to a deep understanding of the Divine. The terms for this kind of sonic representation are the same as those later used for images and music was even used to conceptualize the universe as in the Music of the Spheres, which regards proportions in the movements of celestial bodies as a form of music. That theory later became shared in Europe, as well, when Christian scholars accessed Islamic texts after the fall of Islamic Spain and Italy. So, privileging vision would impose a modern European cultural order onto a completely different, a pre-modern and Islamic understanding of the world.

Was this importance of music depicted in art works?

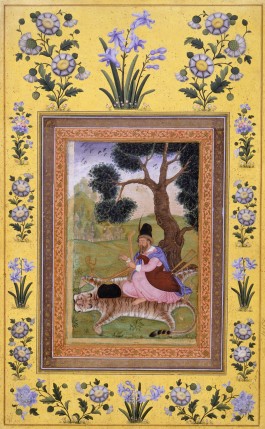

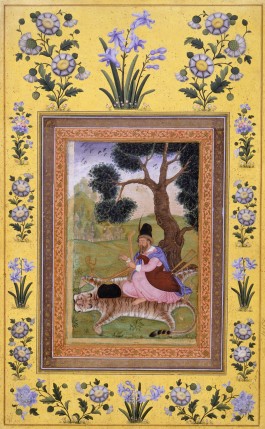

It’s in commentaries, poetry, and later also in art. In his Phaedo, Plato had Socrates deeming philosophy the noblest art and he has a dream redefining philosophy as music. Such episodes made it into Islamic poetry, and there's a Mughal painting from around 1600 that takes it up and shows Plato as a musician. It sets European conventions of representation against the affective sphere of music and thereby compares the mimetic capacity of European painting and music. In that time, there was a frequent attitude, inherited through Platonism, that the Real cannot be accessed through mere imitation, but can be perceived inwardly. Music could enable this form of realism more effectively than painting. For the painter of the miniature, music made knowledge and the divine present and, to him, therefore demonstrated a greater realism than European visual verisimilitude. He documented that understanding in his image: As music exceeded existing knowledge, it was seen as a better way to represent the Real than painting – and of course the “Real” in that time included the divine.

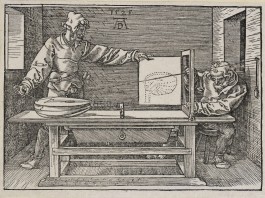

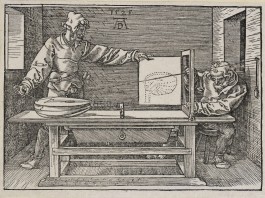

In Europe of the 14th and 15th centuries, perspectival painting emerged as a different tradition of making the divine present. It created an illusion of three-dimensional space on canvas and thereby opened a window to what you describe as the Real that included the divine. In order to really change the paradigms behind knowledge production, you contrast this European central perspective in painting with Islamic geometry, pattern, and ornament. Why is that distinction so important?

Besides being a convention of painting, “perspective” also has a modern history in which it has been treated as a metaphor, an intellectual improvement of representing space on a two-dimensional surface, and therefore a demonstration of the superiority of Western Civilization and progress. We tend to interpret perspectival painting as “realistic” and we’ve become used to utilizing words related to perspective – like point of view, focal point, horizons, – as metaphors for a single subjectivity, usually understood as the right one and the best one. Part of this has been expressed through the understanding of the surface geometries dominant in Islamic arts like ceramic tiles or carpets as “ornamental” or “decorative.” This is partly true – the eleventh century Islamic Platonists who write about geometry say that, like music, geometry expresses its meaning directly, without intermediary theorization. Yet if we use a tile’s geometry as a cultural metaphor in the same way, it helps us envision real cultural change because it foregrounds multiple equal positions instead of a single subjectivity and truth that have marked Europe’s cultural history. Geometric ornament is multifocal, meaning that it doesn’t require a single viewpoint, assimilation, or hierarchy. It allows us to see things next to each other, laterally, infinitely. This ultimately is the purpose of my work: not to eliminate the conventions or categories of understanding that we have, but to recognize them as one of many potential systems of understanding.

© Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin

Preußischer Kulturbesitz (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Photo: Volker-H. Schneider

Digital Copy: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection (M.80.6.7), www.lacma.org

Did a similar metaphor to painted perspective shape European music history?

I find a kind of writing in music history, which seems to focus on biography, emphasizing the so-called “genius” of individuals and the nations they have been made to represent. This seems parallel to a type of art history that focuses on masterpieces and the celebration of culture. Now, I enjoy pretty things, but I’m intellectually much more interested in the historical and intellectual contexts that enable changing forms and meanings. I haven’t found that approach to European music history – it seems to either be very technical, or very celebratory. Another thing I notice is that often music from the Middle East is described as allegedly “lacking” polyphony, just like painting supposedly “lacked” perspective. That betrays a deep Eurocentrism – these European conventions have a particular history but aren’t demonstrations of superiority. Coming from the Middle East, should I say, they only have equally tempered scales, or they only use rhythms divided into 2, 3, and 4, or their perspective can’t even show the structure, and instead only shows surfaces of things?

One of you main objectives is to substantially change our understanding of Islamic culture and to decolonize knowledge. Does your work contain ideas on how to transform and decolonize music for musicians, as well?

Just as in art, it seems to me that the maintenance of musical terms like “classical” enhances the way in which a particular canon is continually reproduced and legitimized as a globally dominant tradition, with seemingly no consciousness that it has a particular history. For example, the laudable effort to bring people together through European classical music at the Barenboim-Said Academy or the performance of European opera on ancient stages… all of these kinds of events are deeply colonial, even though they are often presented as fundamental cultural shifts. In a decolonial framework, European classical music is no more naturally universal than Indonesian or Nigerian or Chinese music. Such universalization normalizes an idea of the classical based on a European image of Greek and Roman antiquity. In a way, this isn’t simply just a rejection of other cultures, but of the intellectual challenges made by modern composers, who wanted to move away from the canon in a multiplicity of ways. Now, while the study of postcolonialism considers the histories of how colonialism has caused change, decolonization essentially means to recoup what has been lost through colonialism, to understand how everything functions outside of the impositions of modernity – taking seriously and learning from non-modern and non-Western ways of experiencing the world. Thinking about how such change is possible, what I discovered in my research is this: the intellectual and creative products of earlier periods are like time capsules of another way, a pre-modern and pre-colonial way of being. Through them I find a means of decolonizing how I think about the world and of course, musicians can enter such time capsules through these texts and artistic practices and incorporate them into their work, too.

How do you envision a transformed music practice that follows that approach and finds new concepts through creative products of earlier periods?

It isn’t enough to simply “expand” the canon by throwing in some non-Western works or inviting some non-Western artists now and again. Even the term “non-Western” has this huge baggage of colonialism, this us-and-them. If you want fundamental change, what I imagine would be more edifying might be to actually include the structures of various musical traditions within programs of music education. Engage with multiple practices of instruction, documentation, and theorization of music rather than basing everything on difference. What happens if we learn from each other, eye to eye, on an even playing field? What if we actually learn and exchange? Such decolonization is my learning how a taksim works on the oud, it is musicians figuring out how to play an Achaemenid flute, it is a rapper in Nairobi, it is K-Pop. It is people negotiating conventions of sound with various ranges of experience and levels of skill. I think there are actually a lot of examples of this shift in the musical context, partly because the performative nature of music can enable enormous experimentalism and a hunger for learning. Going back to where this conversation started, this desire for growth and change through equal exchange is at the heart of Plato’s dialogues, and it is absolutely necessary for both equality and democracy to function.

Wendy M. K. Shaw

Photo © Bernd Wannenmacher

You talked about the power of conventions: What does it need, on the other side, to decolonize our listening habits?

I think this model would look like the playlist on a lot of our devices. Mine switches between Bach and Oud Taksims and Ligeti and hip hop and Carla Bruni and Hamilton and Beethoven and Abba and Annie Lennox and Nina Simone and Curtis Mayfield and Zeki Müren and Dolly Parton and Anouar Brahem and and and. If we take multifocality as a pattern for change, it means that we allow for difference on an even playing field of class, location, race, gender, and so on. A geometric ornament inspires us to let go of hierarchies, even ideally those that prioritize ourselves, and at least temporarily prioritizing the position that we are not in. There’s this strange thing that people like to hear the same music they know. And obviously, this is comforting, we can sing along, compare performances. But there’s no need for this model of music-as-lullaby to be the only aspect of musical appreciation. How can you even know what you like when you resist engaging anything you don’t already know except on your own terms? Multifocality means welcoming the other as the self. It means not simply tolerating, but truly respecting what you don’t already know, and perhaps don’t understand. I use the metaphor of Islamic pattern to model this shift. How do you do it? You refuse to shut yourself off from difference. You embrace the unfamiliar. ¶

“What happens when we let go of our traditions? We become new ones.” In her Outernational Listening Session “Sounding Changes” at Radialsystem Berlin, Wendy M. K. Shaw thinks about such becoming through letting go. Change is a vital theme for her, a scholar of the art of Islamic cultures, whose most recent book, “What is ‘Islamic’ Art? Between Religion and Perception,” attempts to transform our understanding of how perception functioned in the pre-colonial Islamic world. Letting go of conventional categories for the arts, she considers music to understand images and representation in a culture whose primary sensory organ was the heart. How can her work be used as a toolbox for artists and musicians, who are looking for means of sliding free from the straightjackets of cultural and genre categories? And what’s the sound of a decolonized music practice? A conversation about cultural change through time traveling to the past, the connections of listening and seeing, and how Islamic ornament can serve the decolonization of music.

By Philip Geisler

Title Image © Erik Albers

Your current research evolves around the question of what pre-modern “Islamic” art is. Why do you deal with music in order find out about that?

While public discussions of Islam often talk about an image prohibition, there have been many pictures in Islamic cultures. This misconception is pretty surprising – I try to address how it emerged and persists, but what is more interesting to me is how people understand these images as producing meaning. As I was investigating this question for the image in Islam by reading the Qur’an, religious commentaries, philosophy, and poetry, I realized that limiting art through the visual image, privileging vision in that way, is a modern European practice. As in antiquity, in a tradition that travels through the thought of Plato into Late Antiquity in which Islam emerged, the heart, not the eye, was the primary sensory organ, and the ear was a central vehicle to it. Most early commentaries about permissibility of the arts in Islam are about music. These give a good idea about how music was understood as intoxicating, potentially leading people astray but also potentially leading them to a deep understanding of the Divine. The terms for this kind of sonic representation are the same as those later used for images and music was even used to conceptualize the universe as in the Music of the Spheres, which regards proportions in the movements of celestial bodies as a form of music. That theory later became shared in Europe, as well, when Christian scholars accessed Islamic texts after the fall of Islamic Spain and Italy. So, privileging vision would impose a modern European cultural order onto a completely different, a pre-modern and Islamic understanding of the world.

Was this importance of music depicted in art works?

It’s in commentaries, poetry, and later also in art. In his Phaedo, Plato had Socrates deeming philosophy the noblest art and he has a dream redefining philosophy as music. Such episodes made it into Islamic poetry, and there's a Mughal painting from around 1600 that takes it up and shows Plato as a musician. It sets European conventions of representation against the affective sphere of music and thereby compares the mimetic capacity of European painting and music. In that time, there was a frequent attitude, inherited through Platonism, that the Real cannot be accessed through mere imitation, but can be perceived inwardly. Music could enable this form of realism more effectively than painting. For the painter of the miniature, music made knowledge and the divine present and, to him, therefore demonstrated a greater realism than European visual verisimilitude. He documented that understanding in his image: As music exceeded existing knowledge, it was seen as a better way to represent the Real than painting – and of course the “Real” in that time included the divine.

In Europe of the 14th and 15th centuries, perspectival painting emerged as a different tradition of making the divine present. It created an illusion of three-dimensional space on canvas and thereby opened a window to what you describe as the Real that included the divine. In order to really change the paradigms behind knowledge production, you contrast this European central perspective in painting with Islamic geometry, pattern, and ornament. Why is that distinction so important?

Besides being a convention of painting, “perspective” also has a modern history in which it has been treated as a metaphor, an intellectual improvement of representing space on a two-dimensional surface, and therefore a demonstration of the superiority of Western Civilization and progress. We tend to interpret perspectival painting as “realistic” and we’ve become used to utilizing words related to perspective – like point of view, focal point, horizons, – as metaphors for a single subjectivity, usually understood as the right one and the best one. Part of this has been expressed through the understanding of the surface geometries dominant in Islamic arts like ceramic tiles or carpets as “ornamental” or “decorative.” This is partly true – the eleventh century Islamic Platonists who write about geometry say that, like music, geometry expresses its meaning directly, without intermediary theorization. Yet if we use a tile’s geometry as a cultural metaphor in the same way, it helps us envision real cultural change because it foregrounds multiple equal positions instead of a single subjectivity and truth that have marked Europe’s cultural history. Geometric ornament is multifocal, meaning that it doesn’t require a single viewpoint, assimilation, or hierarchy. It allows us to see things next to each other, laterally, infinitely. This ultimately is the purpose of my work: not to eliminate the conventions or categories of understanding that we have, but to recognize them as one of many potential systems of understanding.

© Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin

Preußischer Kulturbesitz (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Photo: Volker-H. Schneider

Digital Copy: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection (M.80.6.7), www.lacma.org

Did a similar metaphor to painted perspective shape European music history?

I find a kind of writing in music history, which seems to focus on biography, emphasizing the so-called “genius” of individuals and the nations they have been made to represent. This seems parallel to a type of art history that focuses on masterpieces and the celebration of culture. Now, I enjoy pretty things, but I’m intellectually much more interested in the historical and intellectual contexts that enable changing forms and meanings. I haven’t found that approach to European music history – it seems to either be very technical, or very celebratory. Another thing I notice is that often music from the Middle East is described as allegedly “lacking” polyphony, just like painting supposedly “lacked” perspective. That betrays a deep Eurocentrism – these European conventions have a particular history but aren’t demonstrations of superiority. Coming from the Middle East, should I say, they only have equally tempered scales, or they only use rhythms divided into 2, 3, and 4, or their perspective can’t even show the structure, and instead only shows surfaces of things?

One of you main objectives is to substantially change our understanding of Islamic culture and to decolonize knowledge. Does your work contain ideas on how to transform and decolonize music for musicians, as well?

Just as in art, it seems to me that the maintenance of musical terms like “classical” enhances the way in which a particular canon is continually reproduced and legitimized as a globally dominant tradition, with seemingly no consciousness that it has a particular history. For example, the laudable effort to bring people together through European classical music at the Barenboim-Said Academy or the performance of European opera on ancient stages… all of these kinds of events are deeply colonial, even though they are often presented as fundamental cultural shifts. In a decolonial framework, European classical music is no more naturally universal than Indonesian or Nigerian or Chinese music. Such universalization normalizes an idea of the classical based on a European image of Greek and Roman antiquity. In a way, this isn’t simply just a rejection of other cultures, but of the intellectual challenges made by modern composers, who wanted to move away from the canon in a multiplicity of ways. Now, while the study of postcolonialism considers the histories of how colonialism has caused change, decolonization essentially means to recoup what has been lost through colonialism, to understand how everything functions outside of the impositions of modernity – taking seriously and learning from non-modern and non-Western ways of experiencing the world. Thinking about how such change is possible, what I discovered in my research is this: the intellectual and creative products of earlier periods are like time capsules of another way, a pre-modern and pre-colonial way of being. Through them I find a means of decolonizing how I think about the world and of course, musicians can enter such time capsules through these texts and artistic practices and incorporate them into their work, too.

How do you envision a transformed music practice that follows that approach and finds new concepts through creative products of earlier periods?

It isn’t enough to simply “expand” the canon by throwing in some non-Western works or inviting some non-Western artists now and again. Even the term “non-Western” has this huge baggage of colonialism, this us-and-them. If you want fundamental change, what I imagine would be more edifying might be to actually include the structures of various musical traditions within programs of music education. Engage with multiple practices of instruction, documentation, and theorization of music rather than basing everything on difference. What happens if we learn from each other, eye to eye, on an even playing field? What if we actually learn and exchange? Such decolonization is my learning how a taksim works on the oud, it is musicians figuring out how to play an Achaemenid flute, it is a rapper in Nairobi, it is K-Pop. It is people negotiating conventions of sound with various ranges of experience and levels of skill. I think there are actually a lot of examples of this shift in the musical context, partly because the performative nature of music can enable enormous experimentalism and a hunger for learning. Going back to where this conversation started, this desire for growth and change through equal exchange is at the heart of Plato’s dialogues, and it is absolutely necessary for both equality and democracy to function.

Wendy M. K. Shaw

Photo © Bernd Wannenmacher

You talked about the power of conventions: What does it need, on the other side, to decolonize our listening habits?

I think this model would look like the playlist on a lot of our devices. Mine switches between Bach and Oud Taksims and Ligeti and hip hop and Carla Bruni and Hamilton and Beethoven and Abba and Annie Lennox and Nina Simone and Curtis Mayfield and Zeki Müren and Dolly Parton and Anouar Brahem and and and. If we take multifocality as a pattern for change, it means that we allow for difference on an even playing field of class, location, race, gender, and so on. A geometric ornament inspires us to let go of hierarchies, even ideally those that prioritize ourselves, and at least temporarily prioritizing the position that we are not in. There’s this strange thing that people like to hear the same music they know. And obviously, this is comforting, we can sing along, compare performances. But there’s no need for this model of music-as-lullaby to be the only aspect of musical appreciation. How can you even know what you like when you resist engaging anything you don’t already know except on your own terms? Multifocality means welcoming the other as the self. It means not simply tolerating, but truly respecting what you don’t already know, and perhaps don’t understand. I use the metaphor of Islamic pattern to model this shift. How do you do it? You refuse to shut yourself off from difference. You embrace the unfamiliar. ¶

Wir nutzen die von dir eingegebene E-Mail-Adresse, um dir in regelmäßigen Abständen unseren Newsletter senden zu können. Falls du es dir mal anders überlegst und keine Newsletter mehr von uns bekommen möchtest, findest du in jeder Mail in der Fußzeile einen Unsubscribe-Button. Damit kannst du deine E-Mail-Adresse aus unserem Verteiler löschen. Weitere Infos zum Thema Datenschutz findest du in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

OUTERNATIONAL wird kuratiert von Elisa Erkelenz und ist ein Kooperationsprojekt von PODIUM Esslingen und VAN Magazin im Rahmen des Fellowship-Programms #bebeethoven anlässlich des Beethoven-Jubiläums 2020 – maßgeblich gefördert von der Kulturstiftung des Bundes sowie dem Land Baden-Württemberg, der Baden-Württemberg Stiftung und der L-Bank.

Wir nutzen die von dir eingegebene E-Mail-Adresse, um dir in regelmäßigen Abständen unseren Newsletter senden zu können. Falls du es dir mal anders überlegst und keine Newsletter mehr von uns bekommen möchtest, findest du in jeder Mail in der Fußzeile einen Unsubscribe-Button. Damit kannst du deine E-Mail-Adresse aus unserem Verteiler löschen. Weitere Infos zum Thema Datenschutz findest du in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

OUTERNATIONAL wird kuratiert von Elisa Erkelenz und ist ein Kooperationsprojekt von PODIUM Esslingen und VAN Magazin im Rahmen des Fellowship-Programms #bebeethoven anlässlich des Beethoven-Jubiläums 2020 – maßgeblich gefördert von der Kulturstiftung des Bundes sowie dem Land Baden-Württemberg, der Baden-Württemberg Stiftung und der L-Bank.