By Philip Geisler

The Tehran-based composer Arshia Samsaminia sits in front of an electric guitar and a Darth Vader mask – two hints that he has dedicated his artistic life to sonic textures, timbres, and technology. As Iran’s pre-eminent dastgah tradition was modernized in the early 20th century, it lost many of its complex microtonal intervals. Samsaminia explores pre-modern music theories and uses software to excavate the forgotten frequencies and expand contemporary compositional expression. His most recent piece “FREQ.EXP” was just celebrated at this year’s Klangteppich Festival where viola player Nikolaus Schlierf, one of two performers, bathed listeners in stretched overtones and layered sound phenomena that escaped the clichés of what is commonly seen as Persian music. A conversation about the knowledge embedded in notation, the bias of technology, and replicating music that resists standardization.

OUTERNATIONAL: Arshia, what are some formative memories that come to your mind when you think of your first years of practicing music as a teenager?

Arshia Samsaminia: I was studying at the Tehran music school when I was 13 and chose the sitar and tar as mandatory Persian instruments. Both of them are based on improvisation, so I learned lots of dastgah figures and melodies from my professors heart to heart. It was a way of learning Persian music by listening to and repeating your professor as ustad, or maestro.

How did notated sheets enter your learning process?

Arshia: Without knowing any graphical score or having any skill of notating contemporary music whatsoever, I developed an inner urge to write down my improvisations to remember what I played. So I developed my own graphical style. That was the first moment when I thought that I should start composing music on paper. I never showed this to my teachers.

Nikolaus, you grew up in Kötzing, a town in the Bavarian Forest. How closely was your musical becoming connected to notation?

Nikolaus Schlierf: I remember practicing Carl Orff's Christmas Story on recorders and Orff instruments when I couldn't read yet. Interestingly, that music was also played to me and I learned the parts by repetition. Notation came in later in the children's choir. My violin lessons and classical viola studies then were entirely based on notation. Fortunately, children in Germany today are more often encouraged to just start playing and see what the instrument has to offer. I needed good teachers at a late stage of my musical education. After intensive studies, you do not dare to leave the comfort zone of notation so easily. You want to see what you're playing.

Arshia, why did you hide your notations from your teachers?

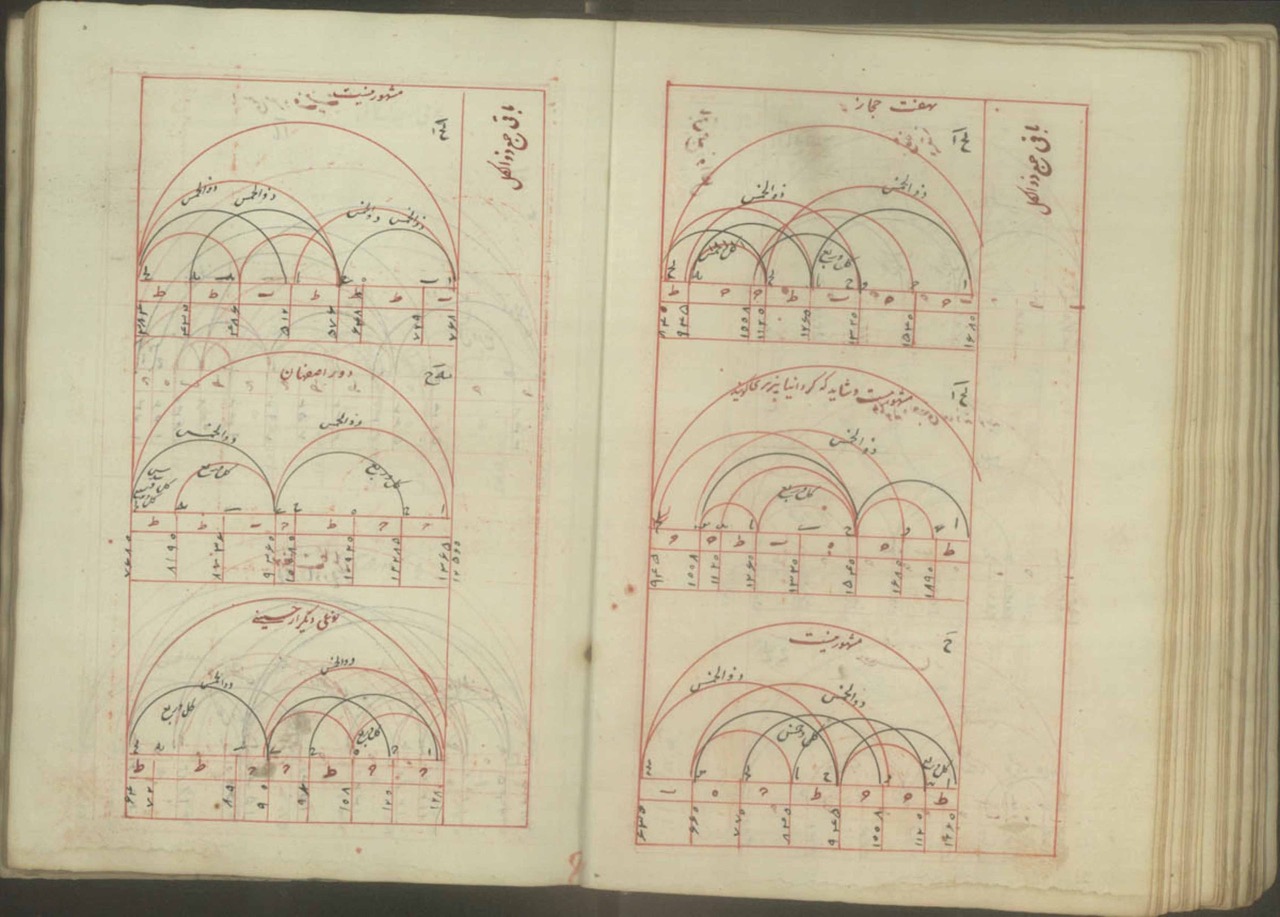

Arshia: They believed that you should have these improvisations in your blood. What counts is replicating traditions by imitating your teachers. This is a philosophical attitude from ancient times, because there was no general notational system. There were different approaches to notating dastgah music between the 10th and 13th centuries. My compositions and my doctoral research explore how we can use the ratios, frequencies, and scales of this time in contemporary music. You find many books with figures from that period, in which polymaths like Al-Shirazi, Al-Farabi, Al-Urmawi, and Ibn Sina developed notational systems based on the Persian alphabet. Each letter showed a distinct frequency. I transcribe these early ways of indicating dastgah intervals through electronic calculations of the frequencies that these authors described in their letter-based notations. This pre-modern music was based on overtones, a huge diversity of scales, and much more than the 24 equal divisions of an octave that are taught at Iranian music schools today. Most traditional music that you hear from the 1930s until today is based on a modernized idiom introduced about 100 years ago by Ali-Naqi Vaziri, who reduced the richness of Persian music by tempering instruments and applying accidentals and equal divisions of an octave that he had learned in Paris.

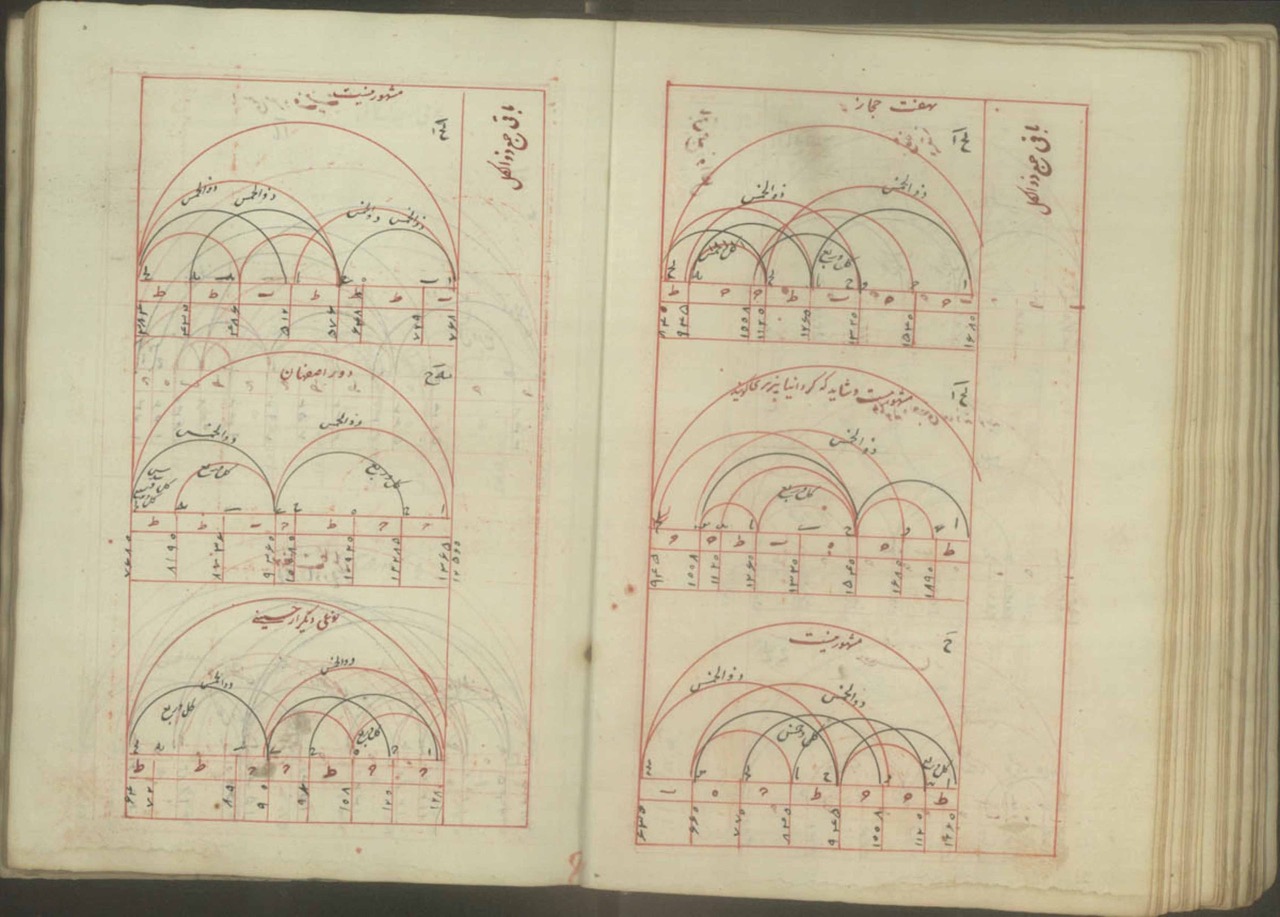

Interval calculations in Al-Shirazi’s book Dorrat al-tāj by Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, AD 1306 (AH 705).

You both collaborated during Arshia’s residency at Klangteppich 2022, the Berlin-based Festival of Music of the Iranian Diaspora. Nikolaus, you performed Arshia’s new electroacoustic composition “FREQ.EXP” together with Johannes Fink. How has that piece expanded your thinking about the knowledge that is embedded in notation?

Nikolaus: In terms of structure, it was familiar to me. But how Arshia notates where and how to find individual notes on the string was completely new to me. I had to spend a lot of time searching for tones on the viola. The working process of this notation is much more about evolution. We recorded our rehearsals and sent them to Arshia, we talked a lot with each other. The piece continued to evolve in the rehearsal process. A lot happened on the sheet with which I played the premiere!

Evolving music. Annotations in Nikolaus Schlierf’s sheet music for »FREQ.EXP«

How did Arshia’s sheet music for “FREQ.EXP” alter the skills by which you handle your instruments?

Nikolaus: From a technical point of view, high harmonics like a 15th overtone change your practice. You have to expand your handling of the instrument and think differently about the string, your own finger, and gravity. The path to the tone is part of the notation. We noticed during rehearsals how differently we play our instruments when we slowly slide into overtones. Holding an overtone for more than two minutes is very delicate. It requires incredible concentration and a completely different body tension. The notation makes you learn at the same time as your body forgets familiar patterns.

There are diverse pre-modern music theories on dastgah, there are modern forms of dastgah reinterpreted through global interactions, and there is the contemporary music practice in Iran. So as for all forms of cultural heritage, there is no single ‘authentic’ origin, but it was an evolving discourse. How do you decide which dastgah you take as the basis for your compositions and your notational system, Arshia?

Arshia: The Persian and Arab polymaths always started their theories by expressing great respect for previous thinkers only to disagree with them on the next page, where they presented their own approach to intervals. So you have to work out different notational solutions for individual polymaths. For “FREQ.EXP” and another recent composition that premiered with Collegium Novum Zurich last month, my source was Ibn Sina. For the electronic and the acoustic part of the pieces, I used software to calculate the precise 18 octaval frequencies that Ibn Sina proposed.

In pre-modern dastgah, the musician’s ear was key to the music. We could also say the music was rooted in individual perception, which showed most in the circumstance that musicians tuned their instruments by ear. How do you work around this lack of temperament?

Arshia: There are two ways of reproducing the healthy fundamental note based on the proposed pre-modern scales. One is to give musicians sonic cues through electronics. You use software that calculates the precise frequencies, scales, and the ratios of tiny intervals. Marc Sabat taught me that this process of finding the right tone can be part of the composition and can make the musical performance more intriguing. The second way is to detune string instruments or use multiphonics, a different mouthpiece, or change how woodwind players press their lips.

We often see electronics as neutral even though there is always a cultural bias embedded in algorithms and software technologies, as well. How much do you have to push the boundaries of notation software and electronic instruments in your contemporary adaptation of dastgahs?

Arshia: I work around this bias in technology by privileging acoustics. I build on electronics only whenever I cannot produce a specific sound quality with acoustic instruments. In my electro-acoustic pieces, electronics serve very defined aesthetic goals and support acoustic instruments.

»My work is not about advertising an exoticized music for a touristic gaze. It is about the expanded depth and psycho-acoustic potential that lies in the notes and intervals.«

So you use electronics to solve the need for replicability of a music that eschews standardization. Why do you dedicate so much of your work to bringing these two into harmony?

Arshia: It is quite easy for Iranian musicians to find the right microtonal notes because we hear these notes from our childhood onwards. Still, most traditional ensembles today perform in unison, even though the original materials were notated vertically with rich intervals. My goal is to bring this richness to a global level and enable musicians from different musical cultures to play music with these microtones. It’s a forgotten complexity that we can still find in ancient books.

In a certain sense, you work like an archaeologist. Do you actually find new sonic shards while excavating these sound concepts buried during modernization?

Arshia: When I transcribed Ibn Sina’s notation system, I found lots of new sound phenomena, frequency beatings, and very smooth harmonics. Finding new frequencies as additional compositional material is essentially the potential that Persian music holds for musicians and composers around the world. My work is not about advertising an exoticized music for a touristic gaze. It is about the expanded depth and psycho-acoustic potential that lies in the notes and intervals.

»It is quite easy for Iranian musicians to find the right microtonal notes because we hear these notes from our childhood onwards. Still, most traditional ensembles today perform in unison, even though the original materials were notated vertically with rich intervals. My goal is to bring this richness to a global level and enable musicians from different musical cultures to play music with these microtones. It’s a forgotten complexity that we can still find in ancient books.«

European colonialism often appropriated non-European art forms for artistic innovation that served Western artists and powers. You seem to be wanting to expand dastgah music. But that universality is routed through European notation, to which you adapt the music. How do you think about ownership and cultural dominance in your work?

Arshia: Ownership can play out in narrow ways, where there is a determination for me as an Iranian composer to create pieces that feel like pistachio or saffron to a commissioner. But my work in connecting microtonal traditions and contemporary music evolved from the sheer excitement over intervals and scale dimensions in Persian music. Instead of cultural identity or national possession, musical ownership for me concerns my global community of microtonal composers, who can expand their expressive means by using my systemization of dastgah.

In a recent essay for norient, you explain that you aim to use notation as a way to convey the dastgah micro-intervals to performers regardless of their cultural background. Did the two of you gain insights during your collaboration into the extent to which this bypassing of cultural context can really work?

Arshia: With precise calculation on a microtonal and harmonic level, the cultural background is less important. But the score of my Klangteppich composition has very few indications of dynamics. So while tones and timings are precise, there is a lot of space for interpretation. The feeling that performers give to my pieces depends profoundly on cultural background.

Nikolaus: In free parts, when more communication has to happen, musical background and cultural knowledge play a big role. When you intuitively create the music in dialogue, it depends a lot on which interpreter plays with which musical profile. But when you play the space of a quarter tone over two minutes very slowly, it's incredible how big this little interval can become. The further you enter this large space of microtonality, the more cultural attributions of music dissolve. In microtonal spheres, it no longer matters much where you come from. ¶

This text is part of VAN Outernational #21 published in coopration with »Klangteppich. Festival for music of the Iranian diaspora IV«. Klangteppich is funded by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (German Federal Cultural Foundation), by the Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien (Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media) and the Co-financing fund Berlin.

By Philip Geisler

The Tehran-based composer Arshia Samsaminia sits in front of an electric guitar and a Darth Vader mask – two hints that he has dedicated his artistic life to sonic textures, timbres, and technology. As Iran’s pre-eminent dastgah tradition was modernized in the early 20th century, it lost many of its complex microtonal intervals. Samsaminia explores pre-modern music theories and uses software to excavate the forgotten frequencies and expand contemporary compositional expression. His most recent piece “FREQ.EXP” was just celebrated at this year’s Klangteppich Festival where viola player Nikolaus Schlierf, one of two performers, bathed listeners in stretched overtones and layered sound phenomena that escaped the clichés of what is commonly seen as Persian music. A conversation about the knowledge embedded in notation, the bias of technology, and replicating music that resists standardization.

OUTERNATIONAL: Arshia, what are some formative memories that come to your mind when you think of your first years of practicing music as a teenager?

Arshia Samsaminia: I was studying at the Tehran music school when I was 13 and chose the sitar and tar as mandatory Persian instruments. Both of them are based on improvisation, so I learned lots of dastgah figures and melodies from my professors heart to heart. It was a way of learning Persian music by listening to and repeating your professor as ustad, or maestro.

How did notated sheets enter your learning process?

Arshia: Without knowing any graphical score or having any skill of notating contemporary music whatsoever, I developed an inner urge to write down my improvisations to remember what I played. So I developed my own graphical style. That was the first moment when I thought that I should start composing music on paper. I never showed this to my teachers.

Nikolaus, you grew up in Kötzing, a town in the Bavarian Forest. How closely was your musical becoming connected to notation?

Nikolaus Schlierf: I remember practicing Carl Orff's Christmas Story on recorders and Orff instruments when I couldn't read yet. Interestingly, that music was also played to me and I learned the parts by repetition. Notation came in later in the children's choir. My violin lessons and classical viola studies then were entirely based on notation. Fortunately, children in Germany today are more often encouraged to just start playing and see what the instrument has to offer. I needed good teachers at a late stage of my musical education. After intensive studies, you do not dare to leave the comfort zone of notation so easily. You want to see what you're playing.

Arshia, why did you hide your notations from your teachers?

Arshia: They believed that you should have these improvisations in your blood. What counts is replicating traditions by imitating your teachers. This is a philosophical attitude from ancient times, because there was no general notational system. There were different approaches to notating dastgah music between the 10th and 13th centuries. My compositions and my doctoral research explore how we can use the ratios, frequencies, and scales of this time in contemporary music. You find many books with figures from that period, in which polymaths like Al-Shirazi, Al-Farabi, Al-Urmawi, and Ibn Sina developed notational systems based on the Persian alphabet. Each letter showed a distinct frequency. I transcribe these early ways of indicating dastgah intervals through electronic calculations of the frequencies that these authors described in their letter-based notations. This pre-modern music was based on overtones, a huge diversity of scales, and much more than the 24 equal divisions of an octave that are taught at Iranian music schools today. Most traditional music that you hear from the 1930s until today is based on a modernized idiom introduced about 100 years ago by Ali-Naqi Vaziri, who reduced the richness of Persian music by tempering instruments and applying accidentals and equal divisions of an octave that he had learned in Paris.

Interval calculations in Al-Shirazi’s book Dorrat al-tāj by Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, AD 1306 (AH 705).

You both collaborated during Arshia’s residency at Klangteppich 2022, the Berlin-based Festival of Music of the Iranian Diaspora. Nikolaus, you performed Arshia’s new electroacoustic composition “FREQ.EXP” together with Johannes Fink. How has that piece expanded your thinking about the knowledge that is embedded in notation?

Nikolaus: In terms of structure, it was familiar to me. But how Arshia notates where and how to find individual notes on the string was completely new to me. I had to spend a lot of time searching for tones on the viola. The working process of this notation is much more about evolution. We recorded our rehearsals and sent them to Arshia, we talked a lot with each other. The piece continued to evolve in the rehearsal process. A lot happened on the sheet with which I played the premiere!

Evolving music. Annotations in Nikolaus Schlierf’s sheet music for »FREQ.EXP«

How did Arshia’s sheet music for “FREQ.EXP” alter the skills by which you handle your instruments?

Nikolaus: From a technical point of view, high harmonics like a 15th overtone change your practice. You have to expand your handling of the instrument and think differently about the string, your own finger, and gravity. The path to the tone is part of the notation. We noticed during rehearsals how differently we play our instruments when we slowly slide into overtones. Holding an overtone for more than two minutes is very delicate. It requires incredible concentration and a completely different body tension. The notation makes you learn at the same time as your body forgets familiar patterns.

There are diverse pre-modern music theories on dastgah, there are modern forms of dastgah reinterpreted through global interactions, and there is the contemporary music practice in Iran. So as for all forms of cultural heritage, there is no single ‘authentic’ origin, but it was an evolving discourse. How do you decide which dastgah you take as the basis for your compositions and your notational system, Arshia?

Arshia: The Persian and Arab polymaths always started their theories by expressing great respect for previous thinkers only to disagree with them on the next page, where they presented their own approach to intervals. So you have to work out different notational solutions for individual polymaths. For “FREQ.EXP” and another recent composition that premiered with Collegium Novum Zurich last month, my source was Ibn Sina. For the electronic and the acoustic part of the pieces, I used software to calculate the precise 18 octaval frequencies that Ibn Sina proposed.

In pre-modern dastgah, the musician’s ear was key to the music. We could also say the music was rooted in individual perception, which showed most in the circumstance that musicians tuned their instruments by ear. How do you work around this lack of temperament?

Arshia: There are two ways of reproducing the healthy fundamental note based on the proposed pre-modern scales. One is to give musicians sonic cues through electronics. You use software that calculates the precise frequencies, scales, and the ratios of tiny intervals. Marc Sabat taught me that this process of finding the right tone can be part of the composition and can make the musical performance more intriguing. The second way is to detune string instruments or use multiphonics, a different mouthpiece, or change how woodwind players press their lips.

We often see electronics as neutral even though there is always a cultural bias embedded in algorithms and software technologies, as well. How much do you have to push the boundaries of notation software and electronic instruments in your contemporary adaptation of dastgahs?

Arshia: I work around this bias in technology by privileging acoustics. I build on electronics only whenever I cannot produce a specific sound quality with acoustic instruments. In my electro-acoustic pieces, electronics serve very defined aesthetic goals and support acoustic instruments.

»My work is not about advertising an exoticized music for a touristic gaze. It is about the expanded depth and psycho-acoustic potential that lies in the notes and intervals.«

So you use electronics to solve the need for replicability of a music that eschews standardization. Why do you dedicate so much of your work to bringing these two into harmony?

Arshia: It is quite easy for Iranian musicians to find the right microtonal notes because we hear these notes from our childhood onwards. Still, most traditional ensembles today perform in unison, even though the original materials were notated vertically with rich intervals. My goal is to bring this richness to a global level and enable musicians from different musical cultures to play music with these microtones. It’s a forgotten complexity that we can still find in ancient books.

In a certain sense, you work like an archaeologist. Do you actually find new sonic shards while excavating these sound concepts buried during modernization?

Arshia: When I transcribed Ibn Sina’s notation system, I found lots of new sound phenomena, frequency beatings, and very smooth harmonics. Finding new frequencies as additional compositional material is essentially the potential that Persian music holds for musicians and composers around the world. My work is not about advertising an exoticized music for a touristic gaze. It is about the expanded depth and psycho-acoustic potential that lies in the notes and intervals.

»It is quite easy for Iranian musicians to find the right microtonal notes because we hear these notes from our childhood onwards. Still, most traditional ensembles today perform in unison, even though the original materials were notated vertically with rich intervals. My goal is to bring this richness to a global level and enable musicians from different musical cultures to play music with these microtones. It’s a forgotten complexity that we can still find in ancient books.«

European colonialism often appropriated non-European art forms for artistic innovation that served Western artists and powers. You seem to be wanting to expand dastgah music. But that universality is routed through European notation, to which you adapt the music. How do you think about ownership and cultural dominance in your work?

Arshia: Ownership can play out in narrow ways, where there is a determination for me as an Iranian composer to create pieces that feel like pistachio or saffron to a commissioner. But my work in connecting microtonal traditions and contemporary music evolved from the sheer excitement over intervals and scale dimensions in Persian music. Instead of cultural identity or national possession, musical ownership for me concerns my global community of microtonal composers, who can expand their expressive means by using my systemization of dastgah.

In a recent essay for norient, you explain that you aim to use notation as a way to convey the dastgah micro-intervals to performers regardless of their cultural background. Did the two of you gain insights during your collaboration into the extent to which this bypassing of cultural context can really work?

Arshia: With precise calculation on a microtonal and harmonic level, the cultural background is less important. But the score of my Klangteppich composition has very few indications of dynamics. So while tones and timings are precise, there is a lot of space for interpretation. The feeling that performers give to my pieces depends profoundly on cultural background.

Nikolaus: In free parts, when more communication has to happen, musical background and cultural knowledge play a big role. When you intuitively create the music in dialogue, it depends a lot on which interpreter plays with which musical profile. But when you play the space of a quarter tone over two minutes very slowly, it's incredible how big this little interval can become. The further you enter this large space of microtonality, the more cultural attributions of music dissolve. In microtonal spheres, it no longer matters much where you come from. ¶

This text is part of VAN Outernational #21 published in coopration with »Klangteppich. Festival for music of the Iranian diaspora IV«. Klangteppich is funded by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (German Federal Cultural Foundation), by the Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien (Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media) and the Co-financing fund Berlin.

Wir nutzen die von dir eingegebene E-Mail-Adresse, um dir in regelmäßigen Abständen unseren Newsletter senden zu können. Falls du es dir mal anders überlegst und keine Newsletter mehr von uns bekommen möchtest, findest du in jeder Mail in der Fußzeile einen Unsubscribe-Button. Damit kannst du deine E-Mail-Adresse aus unserem Verteiler löschen. Weitere Infos zum Thema Datenschutz findest du in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

OUTERNATIONAL wird kuratiert von Elisa Erkelenz und ist ein Kooperationsprojekt von PODIUM Esslingen und VAN Magazin im Rahmen des Fellowship-Programms #bebeethoven anlässlich des Beethoven-Jubiläums 2020 – maßgeblich gefördert von der Kulturstiftung des Bundes sowie dem Land Baden-Württemberg, der Baden-Württemberg Stiftung und der L-Bank.

Wir nutzen die von dir eingegebene E-Mail-Adresse, um dir in regelmäßigen Abständen unseren Newsletter senden zu können. Falls du es dir mal anders überlegst und keine Newsletter mehr von uns bekommen möchtest, findest du in jeder Mail in der Fußzeile einen Unsubscribe-Button. Damit kannst du deine E-Mail-Adresse aus unserem Verteiler löschen. Weitere Infos zum Thema Datenschutz findest du in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

OUTERNATIONAL wird kuratiert von Elisa Erkelenz und ist ein Kooperationsprojekt von PODIUM Esslingen und VAN Magazin im Rahmen des Fellowship-Programms #bebeethoven anlässlich des Beethoven-Jubiläums 2020 – maßgeblich gefördert von der Kulturstiftung des Bundes sowie dem Land Baden-Württemberg, der Baden-Württemberg Stiftung und der L-Bank.