By Sharon Chan

Translation Zack Ferriday

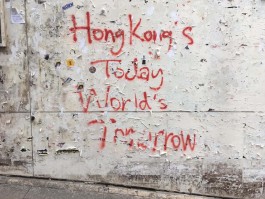

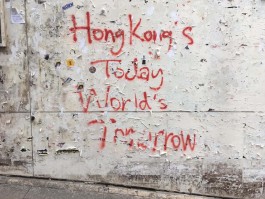

Title Image © Charles Kwong

Hong Kong has enjoyed a high degree of autonomy from China, the city’s sovereign state, since its 1997 handover from the United Kingdom. Beijing’s tightening grip on the city has, however, attracted increasing global attention since June 2019, when a protest movement against the now-suspended extradition bill began to gain pace. Although the enactment of the national security law on June 30, 2020 sparked a strong international reaction, many in Hong Kong have long been alarmed by growing violations of Hong Kong’s autonomous status. From the detention of booksellers by mainland Chinese security agents, to banning democrats from elections, the city’s political freedom is being eroded.

Beijing and the Hong Kong government have stressed that the newly-imposed national security law only applies to “a tiny number of criminals who seriously endanger national security,” and that freedom of expression was well-protected under the Basic Law. But the law, drafted by Beijing and bypassing Hong Kong’s legislature, is rife with ambiguities. People chanting a popular protest slogan could face arrest as the Hong Kong government now identifies it as a call for separatism. The protest anthem Glory to Hong Kong is also banned from schools.

The law also authorizes Beijing’s central government to establish a Hong Kong state security agency that is not subject to the city’s jurisdiction—a legacy of British colonial rule—as well sweeping new police powers. Amnesty International Hong Kong has criticized the manner in which China has pushed through the legislation, and suggests it is to create uncertainty and to govern Hong Kong through fear.

That fear is real. Activists withdrew from pro-democracy groups hours after the law was passed in China’s top legislative body. The encrypted messaging app Signal became the most downloaded app on Google’s Play Store in Hong Kong in July. Over 1,500 cultural workers, plus local and international artists, have signed a joint statement to convey their shock, worry, and anger.

“It seems we have fallen into the era of ‘white terror,’” says Steve Hui (a.k.a. Nerve), a multimedia artist born, raised, and based in Hong Kong. “Many are frustrated because the law appears to have no bounds. At the moment, only activists and pro-democrats are targeted, but we never know whether our works could one day become a target of the regime.” Hui feels that many of his peers are becoming less certain about what they can do creatively. “I am worried because if we, as artists, cannot maintain our visions and have at some point to stop and evaluate the risk of our artistic output, it is a threat to our artistic integrity.”

In 2014, Hui composed and directed 1984, a theatre production which he calls a “cinematic opera,” based on George Orwell’s dystopian novel. By coincidence, the production was premiered at the beginning of the Umbrella Movement, a 79-day Occupy movement demanding universal suffrage in Hong Kong. The opera ends with a scene in which the protagonist stands on a road with her back facing the camera. Although short and subtle, it lent the work a new critical dimension, and connected it to what was happening outside the theatre.

Hui also teaches composition at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, where he emphasizes the cultural and social significance of music and art making. He admits that teaching has becoming more difficult: “I prefer to spend more time in class discussing ideas, topics such as tradition, innovations, and creativity, and what is happening around the world.” He goes on: “I became quite conscious of class discussions after the protest movements, both in 2014 and 2019.”

“The social and political problems that the younger generations face now are something very new to all of us,” he says. The Tiananmen Square Massacre took place in 1989, when Hui was 15 years old. He could not fully comprehend the situation, and started to look for answers in music, literature, and film. Hui believes that the current situation is far more complicated and controversial than when he first started out as a composer: “At least artists did not have to think much about the political consequences of the things they did.” Despite his concern for the younger generations, he also uses the art scene in China as an example to convey hope. “I have been working with artists and xiqu (Chinese opera) troupes in China for some years. Heavy-handed rules do not mean creativity disappears. I see a lot of daring and creative works coming out of such a difficult political landscape”.

When asked if he has any plans of leaving Hong Kong, Hui says he thinks there is still space for creativity in the city and wants to do more. “I would consider leaving though, if the Social Credit System is adopted in Hong Kong.”

Steve-Hui 1984

Photo © The Idealiste

Steve Hui

Photo © Jonathan Crabb

Composer Daniel Lo also shares Hui’s feelings about the new law. “I have been thinking about it a lot. As a Hongkonger I feel very upset. I have not experienced censorship in my artistic career so far, but I can feel the fear growing in the arts scene. I think (classical) music should be able to remain sheltered from political censorship. After all, it is more abstract than other art forms such as theatre and visual art.”

Born in the 1980s, Lo has witnessed numerous changes in Hong Kong; from the transfer of its sovereignty to the political turmoil of recent years. Post-colonial Hong Kong struggles to defend its local history, culture and language from the influence of mainland China. While plenty in Hong Kong—especially the older generations—have a strong Chinese identity, much of Lo’s generation and later identify themselves only with the city.

The rise of “localism” has triggered debates and discussions on Hong Kong identity. An impressive number of localist films have been produced in the past decade. In May of this year, a Kickstarter campaign to raise money for a literature periodical written entirely in Cantonese—Hong Kong’s dominant language—received more than five times its fundraising goal. In the contemporary music scene, more and more Hong Kong composers try to bring the language into their work, ranging from choral works and staged cantatas to operas.

Hong Kong identity has become a focal point of the city’s contemporary culture. Lo’s latest opera, Women Like Us [In 2018, Daniel’s chamber opera A Woman Such as Myself, an English adaptation based on Xi Xi’s short story A Girl Like Me, was premiered in Czech Republic at New Opera Days Ostrava. Women Like Us is a reworking of the script in Cantonese with further developed materials.], is one of a number of vocal works that borrow Cantonese text from Hong Kong writers. The opera is based on two short stories by Xi Xi, one of the city’s most important literary figures:

“Xi Xi’s works address the issue of Hong Kong identity, but what touches me most is the humanistic perspective that makes her works unique. I prefer to distance myself from current issues in my work, because I believe a work with humanistic value would provide another, or even a new perspective to the difficulties and experiences we encounter in our own time,” Lo explains. “Hong Kong has a lot of problems, not just its relationship with China and the loss of freedom of speech. It isn’t healthy for the creative scene if we only focus on one or two subjects.”

Returning from the UK after his PhD studies in 2016, he never thought about staying in the UK. “All my family and friends are in Hong Kong and I truly love this city,” he says. Recently, however, Lo has thought of leaving: “The reality is that as a highly-capitalist city, Hong Kong is becoming increasingly uninhabitable. The charged political atmosphere is not the only reason for me to consider leaving the city I call home.” At the moment he does not know what to expect—he will play it by ear. If the situation prevents him from doing creative work, he will contemplate leaving.

To go or to stay has become a serious consideration for Hongkongers. The final years of the colonial era already saw mass emigration from Hong Kong. Back then, many residents feared that Beijing would not honor its commitments in the Sino-British Joint Declaration. Some later returned after seeing the city maintain its autonomy in the first decade. But now, the security law makes many weigh up whether or not to stay.

Ethnomusicologist Dr. Ho-Chak Law, whose interests include cultural politics and Sinophone transnationalism, decided to leave Hong Kong after a short return from his PhD studies at the University of Michigan in 2018:

“Academia and the music field in Hong Kong are rather conservative. I used to teach the subject ‘Chinese Music’ which is also one of my research interests. The term ‘Chinese’ is by nature political. It usually connotes nationalism, infused with Confucian thinking and sustaining its legitimacy through institutions, conservatories, and commodification,” he says. “But what I see is that music in the Sinophone sphere can be very vibrant and contains a lot of potential. Sadly, the intense social and political atmosphere here has limited the historical imagination of the entire generation. That’s why I want to find a place where I can develop my research in a transnational context. Hong Kong is no longer a suitable place to do so.”

Steve Hui 1984

Photo © unknown

Karen Yu

Photo © unknown

Daniel Lo A Woman Such as Myself

Photo © unknown

He also points out that ideological polarization in Hong Kong is another root cause of the conservative attitude commonly found in the city’s society. “Decolonization does not mean Hong Kong has to embrace and accept everything from mainland China. On the other hand, pro-colonization and counting the good deeds of British colonialism is itself problematic. It is true that the new national security law is a frame that further narrows the space for discussion. But being too self-conscious would only limit our capacity to unpack various pressing social and political issues of Hong Kong, causing polarization to accelerate further.”

Law hopes that people in Hong Kong can put aside their emotional judgement and try not to constrain themselves to only a single perspective for the future. “Hong Kong as a site has many issues awaiting to be unpacked.”

Recent music graduate Karen Yu found herself more eager to explore her identity as an artist amid the social unrest. “The protest movement has somehow provoked me to think about my practice,” she explains. “I asked myself: ‘Do I need to respond to society through my art?”

In February 2020, Yu and Vancouver-based composer William Kuo co-created Augmented Aurality, an installation inspired by the spread of fake news—a phenomenon found widely during the protest movement, which had fueled distrust and even violence in the city.

As Yu established herself as a performer-creator, the national security law swept through Hong Kong. “I had never imagined that I would have to consider the safety of myself and my family for being an artist. When collaborating with people in the past, we talked a lot about artistic concepts and ideas. Strangely, we now tend to talk more about other issues like migration and health. Sometimes I wonder what I would do if one day I held different political views to my collaborators. Would there still be room for collaboration?”

After leaving Hong Kong at the age of 15 to pursue high school, college, and postgraduate education in Canada, Yu decided to return in 2017. “Montreal is not my home. Hong Kong is,” she says. But the deteriorating political situation makes her life and career tougher to navigate. Yu will give herself five years to develop her practice in Hong Kong. But if she can no longer live the way she wants, she too will consider whether Hong Kong is still the place to be. ¶

By Sharon Chan

Translation Zack Ferriday

Title Image © Charles Kwong

Hong Kong has enjoyed a high degree of autonomy from China, the city’s sovereign state, since its 1997 handover from the United Kingdom. Beijing’s tightening grip on the city has, however, attracted increasing global attention since June 2019, when a protest movement against the now-suspended extradition bill began to gain pace. Although the enactment of the national security law on June 30, 2020 sparked a strong international reaction, many in Hong Kong have long been alarmed by growing violations of Hong Kong’s autonomous status. From the detention of booksellers by mainland Chinese security agents, to banning democrats from elections, the city’s political freedom is being eroded.

Beijing and the Hong Kong government have stressed that the newly-imposed national security law only applies to “a tiny number of criminals who seriously endanger national security,” and that freedom of expression was well-protected under the Basic Law. But the law, drafted by Beijing and bypassing Hong Kong’s legislature, is rife with ambiguities. People chanting a popular protest slogan could face arrest as the Hong Kong government now identifies it as a call for separatism. The protest anthem Glory to Hong Kong is also banned from schools.

The law also authorizes Beijing’s central government to establish a Hong Kong state security agency that is not subject to the city’s jurisdiction—a legacy of British colonial rule—as well sweeping new police powers. Amnesty International Hong Kong has criticized the manner in which China has pushed through the legislation, and suggests it is to create uncertainty and to govern Hong Kong through fear.

That fear is real. Activists withdrew from pro-democracy groups hours after the law was passed in China’s top legislative body. The encrypted messaging app Signal became the most downloaded app on Google’s Play Store in Hong Kong in July. Over 1,500 cultural workers, plus local and international artists, have signed a joint statement to convey their shock, worry, and anger.

“It seems we have fallen into the era of ‘white terror,’” says Steve Hui (a.k.a. Nerve), a multimedia artist born, raised, and based in Hong Kong. “Many are frustrated because the law appears to have no bounds. At the moment, only activists and pro-democrats are targeted, but we never know whether our works could one day become a target of the regime.” Hui feels that many of his peers are becoming less certain about what they can do creatively. “I am worried because if we, as artists, cannot maintain our visions and have at some point to stop and evaluate the risk of our artistic output, it is a threat to our artistic integrity.”

In 2014, Hui composed and directed 1984, a theatre production which he calls a “cinematic opera,” based on George Orwell’s dystopian novel. By coincidence, the production was premiered at the beginning of the Umbrella Movement, a 79-day Occupy movement demanding universal suffrage in Hong Kong. The opera ends with a scene in which the protagonist stands on a road with her back facing the camera. Although short and subtle, it lent the work a new critical dimension, and connected it to what was happening outside the theatre.

Hui also teaches composition at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, where he emphasizes the cultural and social significance of music and art making. He admits that teaching has becoming more difficult: “I prefer to spend more time in class discussing ideas, topics such as tradition, innovations, and creativity, and what is happening around the world.” He goes on: “I became quite conscious of class discussions after the protest movements, both in 2014 and 2019.”

“The social and political problems that the younger generations face now are something very new to all of us,” he says. The Tiananmen Square Massacre took place in 1989, when Hui was 15 years old. He could not fully comprehend the situation, and started to look for answers in music, literature, and film. Hui believes that the current situation is far more complicated and controversial than when he first started out as a composer: “At least artists did not have to think much about the political consequences of the things they did.” Despite his concern for the younger generations, he also uses the art scene in China as an example to convey hope. “I have been working with artists and xiqu (Chinese opera) troupes in China for some years. Heavy-handed rules do not mean creativity disappears. I see a lot of daring and creative works coming out of such a difficult political landscape”.

When asked if he has any plans of leaving Hong Kong, Hui says he thinks there is still space for creativity in the city and wants to do more. “I would consider leaving though, if the Social Credit System is adopted in Hong Kong.”

Steve-Hui 1984

Photo © The Idealiste

Steve Hui

Photo © Jonathan Crabb

Composer Daniel Lo also shares Hui’s feelings about the new law. “I have been thinking about it a lot. As a Hongkonger I feel very upset. I have not experienced censorship in my artistic career so far, but I can feel the fear growing in the arts scene. I think (classical) music should be able to remain sheltered from political censorship. After all, it is more abstract than other art forms such as theatre and visual art.”

Born in the 1980s, Lo has witnessed numerous changes in Hong Kong; from the transfer of its sovereignty to the political turmoil of recent years. Post-colonial Hong Kong struggles to defend its local history, culture and language from the influence of mainland China. While plenty in Hong Kong—especially the older generations—have a strong Chinese identity, much of Lo’s generation and later identify themselves only with the city.

The rise of “localism” has triggered debates and discussions on Hong Kong identity. An impressive number of localist films have been produced in the past decade. In May of this year, a Kickstarter campaign to raise money for a literature periodical written entirely in Cantonese—Hong Kong’s dominant language—received more than five times its fundraising goal. In the contemporary music scene, more and more Hong Kong composers try to bring the language into their work, ranging from choral works and staged cantatas to operas.

Hong Kong identity has become a focal point of the city’s contemporary culture. Lo’s latest opera, Women Like Us [In 2018, Daniel’s chamber opera A Woman Such as Myself, an English adaptation based on Xi Xi’s short story A Girl Like Me, was premiered in Czech Republic at New Opera Days Ostrava. Women Like Us is a reworking of the script in Cantonese with further developed materials.], is one of a number of vocal works that borrow Cantonese text from Hong Kong writers. The opera is based on two short stories by Xi Xi, one of the city’s most important literary figures:

“Xi Xi’s works address the issue of Hong Kong identity, but what touches me most is the humanistic perspective that makes her works unique. I prefer to distance myself from current issues in my work, because I believe a work with humanistic value would provide another, or even a new perspective to the difficulties and experiences we encounter in our own time,” Lo explains. “Hong Kong has a lot of problems, not just its relationship with China and the loss of freedom of speech. It isn’t healthy for the creative scene if we only focus on one or two subjects.”

Returning from the UK after his PhD studies in 2016, he never thought about staying in the UK. “All my family and friends are in Hong Kong and I truly love this city,” he says. Recently, however, Lo has thought of leaving: “The reality is that as a highly-capitalist city, Hong Kong is becoming increasingly uninhabitable. The charged political atmosphere is not the only reason for me to consider leaving the city I call home.” At the moment he does not know what to expect—he will play it by ear. If the situation prevents him from doing creative work, he will contemplate leaving.

To go or to stay has become a serious consideration for Hongkongers. The final years of the colonial era already saw mass emigration from Hong Kong. Back then, many residents feared that Beijing would not honor its commitments in the Sino-British Joint Declaration. Some later returned after seeing the city maintain its autonomy in the first decade. But now, the security law makes many weigh up whether or not to stay.

Ethnomusicologist Dr. Ho-Chak Law, whose interests include cultural politics and Sinophone transnationalism, decided to leave Hong Kong after a short return from his PhD studies at the University of Michigan in 2018:

“Academia and the music field in Hong Kong are rather conservative. I used to teach the subject ‘Chinese Music’ which is also one of my research interests. The term ‘Chinese’ is by nature political. It usually connotes nationalism, infused with Confucian thinking and sustaining its legitimacy through institutions, conservatories, and commodification,” he says. “But what I see is that music in the Sinophone sphere can be very vibrant and contains a lot of potential. Sadly, the intense social and political atmosphere here has limited the historical imagination of the entire generation. That’s why I want to find a place where I can develop my research in a transnational context. Hong Kong is no longer a suitable place to do so.”

Steve Hui 1984

Photo © unknown

Karen Yu

Photo © unknown

Daniel Lo A Woman Such as Myself

Photo © unknown

He also points out that ideological polarization in Hong Kong is another root cause of the conservative attitude commonly found in the city’s society. “Decolonization does not mean Hong Kong has to embrace and accept everything from mainland China. On the other hand, pro-colonization and counting the good deeds of British colonialism is itself problematic. It is true that the new national security law is a frame that further narrows the space for discussion. But being too self-conscious would only limit our capacity to unpack various pressing social and political issues of Hong Kong, causing polarization to accelerate further.”

Law hopes that people in Hong Kong can put aside their emotional judgement and try not to constrain themselves to only a single perspective for the future. “Hong Kong as a site has many issues awaiting to be unpacked.”

Recent music graduate Karen Yu found herself more eager to explore her identity as an artist amid the social unrest. “The protest movement has somehow provoked me to think about my practice,” she explains. “I asked myself: ‘Do I need to respond to society through my art?”

In February 2020, Yu and Vancouver-based composer William Kuo co-created Augmented Aurality, an installation inspired by the spread of fake news—a phenomenon found widely during the protest movement, which had fueled distrust and even violence in the city.

As Yu established herself as a performer-creator, the national security law swept through Hong Kong. “I had never imagined that I would have to consider the safety of myself and my family for being an artist. When collaborating with people in the past, we talked a lot about artistic concepts and ideas. Strangely, we now tend to talk more about other issues like migration and health. Sometimes I wonder what I would do if one day I held different political views to my collaborators. Would there still be room for collaboration?”

After leaving Hong Kong at the age of 15 to pursue high school, college, and postgraduate education in Canada, Yu decided to return in 2017. “Montreal is not my home. Hong Kong is,” she says. But the deteriorating political situation makes her life and career tougher to navigate. Yu will give herself five years to develop her practice in Hong Kong. But if she can no longer live the way she wants, she too will consider whether Hong Kong is still the place to be. ¶

Wir nutzen die von dir eingegebene E-Mail-Adresse, um dir in regelmäßigen Abständen unseren Newsletter senden zu können. Falls du es dir mal anders überlegst und keine Newsletter mehr von uns bekommen möchtest, findest du in jeder Mail in der Fußzeile einen Unsubscribe-Button. Damit kannst du deine E-Mail-Adresse aus unserem Verteiler löschen. Weitere Infos zum Thema Datenschutz findest du in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

OUTERNATIONAL wird kuratiert von Elisa Erkelenz und ist ein Kooperationsprojekt von PODIUM Esslingen und VAN Magazin im Rahmen des Fellowship-Programms #bebeethoven anlässlich des Beethoven-Jubiläums 2020 – maßgeblich gefördert von der Kulturstiftung des Bundes sowie dem Land Baden-Württemberg, der Baden-Württemberg Stiftung und der L-Bank.

Wir nutzen die von dir eingegebene E-Mail-Adresse, um dir in regelmäßigen Abständen unseren Newsletter senden zu können. Falls du es dir mal anders überlegst und keine Newsletter mehr von uns bekommen möchtest, findest du in jeder Mail in der Fußzeile einen Unsubscribe-Button. Damit kannst du deine E-Mail-Adresse aus unserem Verteiler löschen. Weitere Infos zum Thema Datenschutz findest du in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

OUTERNATIONAL wird kuratiert von Elisa Erkelenz und ist ein Kooperationsprojekt von PODIUM Esslingen und VAN Magazin im Rahmen des Fellowship-Programms #bebeethoven anlässlich des Beethoven-Jubiläums 2020 – maßgeblich gefördert von der Kulturstiftung des Bundes sowie dem Land Baden-Württemberg, der Baden-Württemberg Stiftung und der L-Bank.